It is impossible to envision Himalayan homes and temples without the swirling smoke or aromatic scent of incense. Despite being a relatively inexpensive everyday item, incense holds significant value in the Tibetan way of life for centuries. Rooted in the Latin word incendere, meaning “set fire to,” and the Middle English word encens, meaning “sweet-smelling substance,” incense releases fragrant smoke when burned for meditation, ceremonies, relaxation, or purification. A plume of smoke rising from burning incense ignites the senses of sight and smell while evoking something spiritual within.

The history of incense spans over 6,000 years, originating from ancient civilizations like Egypt and Mesopotamia. Adopted by various cultures, Tibetan incense-making has endured for over a thousand years as part of the broader tradition of Tibetan medicine, emphasizing natural remedies for holistic healing.

Tibetan incense, found in Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan, is meticulously handcrafted using pure organic materials, often with earthy notes. Traditional recipes sourced from ancient Vedic texts remain unchanged, with fragrant woods like sandalwood, agarwood, pine, or cedar serving as primary ingredients. Herbs, spices, and botanicals further enhance the aroma.

Widely practiced globally, burning incense clears negative energy, aids relaxation, and enhances meditation. Its use in religious ceremonies elevates prayers, while incorporating it into daily routines promotes well-being. Beyond spiritual significance, incense doubles as a natural air freshener and bug repellent, offering a gentle timer as it burns.

Those who use Tibetan incense appreciate the craftsmanship behind it; after all, it is a practice that takes decades to learn and requires a lifetime of devotion. Unlike previous generations, one no longer needs to be a Buddhist monk to produce incense. In the heart of Shambhala, at the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, an incense maker named Parkyid has been studying Tibetan medicine and incense-making for twenty years under his teacher Lobsang Tenzin and has ambitions to start his own incense-making business.

Parkyid makes incense using traditional methods to harvest raw materials from the mountains and produce incense by hand. He makes several arduous trips to collect ingredients that grow wild in the foothills of Yala Snow Mountain, one of the four holy mountains in the Garze region. In addition to navigating challenging terrain and fickle weather, he must be able to identify and distinguish hundreds of plants as each one offers unique scents and medicinal properties. Different parts of the same plant, such as the flower or stem, may be used for Tibetan incense-making. Some recipes even call for the same plant picked in different seasons. The entire process is rooted in Parkyid’s deep understanding and respect for the ingredients and the environment in which they flourish.

Once collected, Parkyid grinds the materials into a paste using water and stones. He avoids the use of machines as they produce higher temperatures; this preserves the fragrance and medicinal qualities of the chosen ingredients. Parkyid uses a hollow ox horn with a narrow opening to pipe the paste into long, even strands. Unlike incense from other parts of the world, Tibetan incense does not have a bamboo stick at the center. Once the incense has dried, the strands are bundled, and the process is complete.

The next time you light incense, take a deep breath. Pause and reflect as the scent transports you to the Himalayas, where materials are still plucked by hand, and connects you to an age-old process. Then take a moment to appreciate the work of dedicated craftspeople, like Parkyid, who ensure that the tradition of Tibetan incense-making endures for centuries to come.

The Life and Legacy of Alexandra David-Néel

In 1924, Alexandra David-Néel made history as one of the first Western women to secretly enter Tibet. Disguised as a beggar, she crossed into Lhasa, bringing the mysteries of Tibetan Buddhism to the West.

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

Since 2023, HIMA JOMO has been steadfast in our pledge to plant a tree in the Himalayas for every perfume purchase made, join us in building a lush forest in the heart of the Himalayas with Nepal Evergreen.

The Travelling Jacket

In 2016, five designers from across South Asia came together to create what is now known as the traveling jacket.

The Himalayan Cedar

This majestic tree has captivated the hearts of explorers, poets, and nature enthusiasts for centuries with its enchanting presence, aromatic fragrance, and enduring qualities that make it a symbol of strength and grace.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Khoma, the Sound of Weaving

A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

Discover Ladakh: The Land of High Passes

India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means land of high passes.

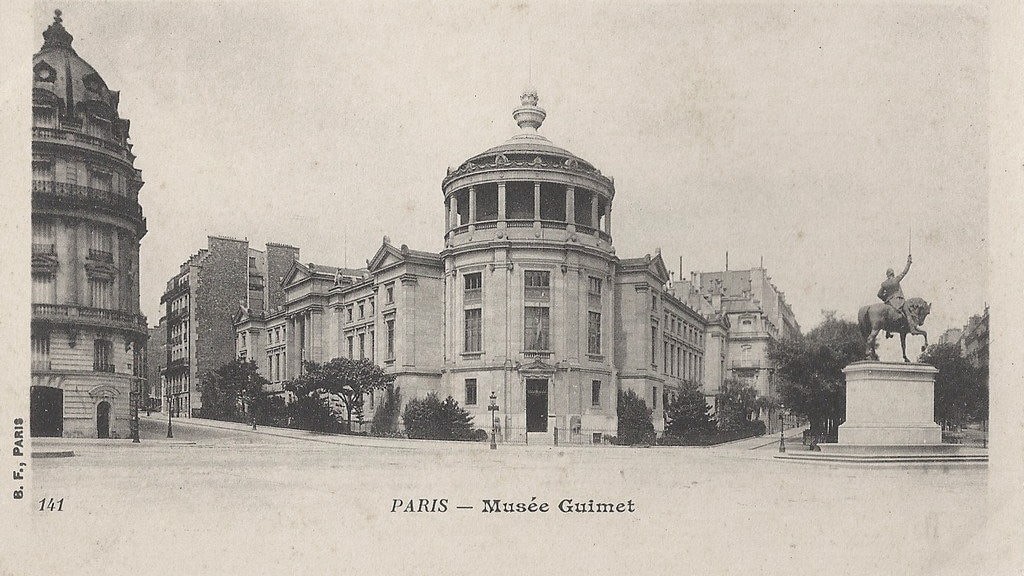

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.