India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities, but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means the land of high passes. Indeed, Ladakh is the highest plateau in India, with most of the land hovering above 3,000 m (9,800 ft.) in elevation. The region, which covers approximately 117,000 square kilometers, offers a remote escape, a cultural melting pot, and an opportunity to imagine life in a bygone era.

Ladakh extends from the Himalayan Ranges to the Kunlun and encompasses the upper Indus River valley. In the present day, Ladakh borders the southwest corner of Xinjiang and Karakoram Pass to the north, Tibet to the east, the Lahaul and Spiti regions to the south, and the Jammu and Baltiyul regions to the west.

The striking peaks of Ladakh, which have long acted as natural borders, were formed over 45 million years ago as the Indian plate was thrust into the more stationary Eurasian plate. Ladakh’s four mountain ranges—the Himalayan, Zanskar, Ladakh, and Karakoram ranges—form a labyrinth of jagged, snow-capped peaks. The region is also home to the Siachen glacier, the largest to exist outside the world’s polar regions, vast azure lakes such as Tso Moriri, and a network of riverways that sustain life in a seemingly barren landscape.

Home to approximately 300,000 people, Ladakh is one of the most sparsely populated regions of India. Leh is both the largest city and present-day capital of Ladakh. It was also the historic capital of the Kingdom of Ladakh, which was ruled from Leh Palace. The palace, which was built in the same style and era as Tibet’s Potala Palace, has been restored in recent years to preserve Ladakhi history and enlighten the region’s visitors. Beyond cities like Leh or Kargil, exist small villages where life revolves around farming and shepherding. Some of these villages still exist deep in mountain valleys without paved roads, requiring a day or more of walking to reach.

Traversing mountain passes has long been a part of life in Ladakh. Historically, Ladakh held a strategic position at the crossroads of important trade routes. Trans-Himalayan caravans would pass through this center of commerce and culture to trade salt, grain, cashmere, indigo, silk, and other precious goods.

With Lhasa only 1,500 km away, it should come as no surprise that there are strong cultural ties between Tibet and Ladakh. Shared traits include ethnicity, religion (Vajrayana Buddhism), crops like barley, and drinks like butter tea and chhang. Since the 13th century, Tibetan people began to migrate and settle in Ladakh, but it’s worth noting that Buddhism originated in India and spread to Tibet via Kashmir and Ladakh. Today, it is still common to see prayer flags fluttering above white monasteries resting high upon Ladakhi foothills.

There are dozens of monasteries scattered throughout Ladakh and some beyond high mountain passes, nestled in valleys without paved roads. Whitewashed stupas, burning juniper offerings, prayer wheels, and prayer flags are common sights in this part of India. Famous monasteries include Hemis monastery, home to the Drukpa or ‘Red Hat’ sect, Thiksey Monastery, which resembles Lhasa’s Potala Palace, and Diskit Monastery, which towers over the Nubra desert valley.

Monasteries may dot the skyline, but Muslims comprise 46.6% of Ladakh’s population and actually outnumber Buddhists. Peaceful coexistence has continued for generations. In places like Leh, mosques occupy the city center while the call to prayer punctuates the day’s rhythms. Jama Masjid, the largest mosque in Ladakh, was erected in the heart of the city in 1667 as a symbol of peace between the Mughals and the Ladakhi King Deldan Magyal. The structure’s Turkish-Iranian architecture adds to Ladakh’s rich and diverse cultural tapestry.

The truth is — there’s much more to Ladakh than its mountains, mosques, and monasteries. Travelers from India and beyond flock to Ladakh for a variety of experiences, from religious pilgrimages and historic tours to motorcycle trips, trekking experiences, and even camel rides in the desert sands of the Nubra valley. Adventurous visitors can be found traversing Umling La, which reaches an elevation of 5,798 m and is known as the world’s highest motorable road in the world. Some visitors are drawn to museums and tourist sites while others prefer to wander through narrow alleyways and bustling markets, bumping elbows with locals clad in traditional gonchas and lapis lazuli necklaces, seeking local delicacies like momos.

Encircled by majestic mountains, Ladakh has been more resistant to rapid commercialism and over-tourism than other parts of India—but not for long. Each day, roads extend deeper into untouched valleys and modern technology replaces ancient ways. Fortunately, efforts are being made to preserve Ladakh’s culture and traditions so that it may remain a cultural haven for generations to come.

Words by Trixie Pacis – Commissioned by hima jomo

The Life and Legacy of Alexandra David-Néel

In 1924, Alexandra David-Néel made history as one of the first Western women to secretly enter Tibet. Disguised as a beggar, she crossed into Lhasa, bringing the mysteries of Tibetan Buddhism to the West.

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

Since 2023, HIMA JOMO has been steadfast in our pledge to plant a tree in the Himalayas for every perfume purchase made, join us in building a lush forest in the heart of the Himalayas with Nepal Evergreen.

The Travelling Jacket

In 2016, five designers from across South Asia came together to create what is now known as the traveling jacket.

The Himalayan Cedar

This majestic tree has captivated the hearts of explorers, poets, and nature enthusiasts for centuries with its enchanting presence, aromatic fragrance, and enduring qualities that make it a symbol of strength and grace.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Khoma, the Sound of Weaving

A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

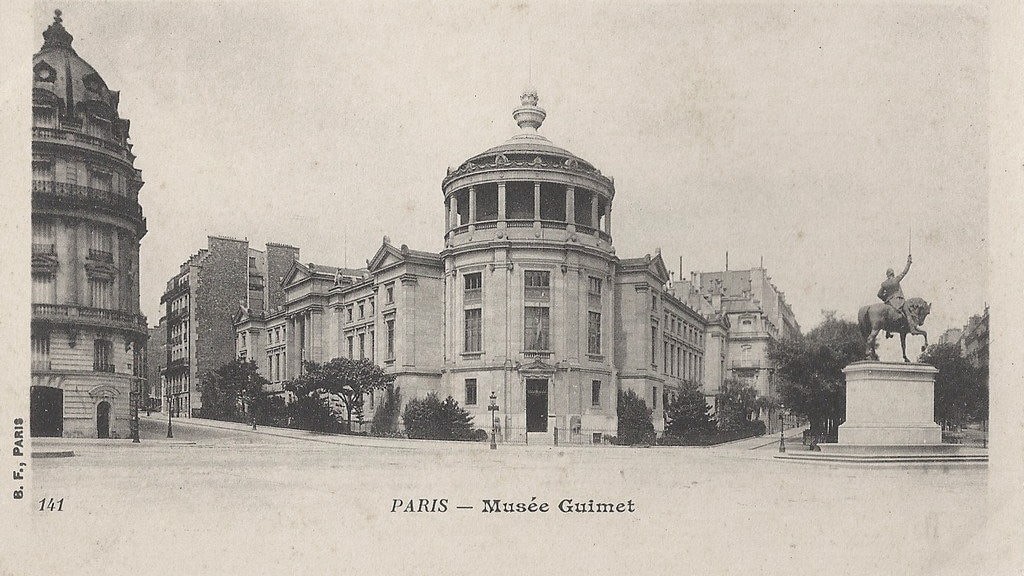

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.

The Power of a Thangka Painting

Thangkas are a distinctly Tibetan form of art centred around religious figures and symbols.