A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

The village of Khoma in the region of Lhuntshe in Bhutan is still an active weaving community whose history lies in the depths of the textiles that were created and are still being woven solely by the women of the community. Bhutan celebrates its textile craftsmanship to this day as the country mandates the wearing of the national attire ‘Gho’ for men and ‘Kira’ for women, which are largely woven on a back-strap loom, hence the practice of this craft is spread across the country.

The weaving community of Khoma is one of the extraordinary villages in Bhutan, where it is apparent that weaving textiles is a lifestyle they’ve adopted and a means of expression. Every single woman from this village is naturally brought up learning and practicing this craft conventionally through kindred bonds with their mothers. It is also known that they specialize in a certain technique of weaving known as the Kishuthara (silk on silk textile) which involves weaving supplementary weft patterns with extra yarns over the constructed base yarn, generally using silk yarn as the base and silk again for constructing the patterns and motifs known as ‘trima’.

Several women in that community have mastered the art of weaving Kishuthara which takes years of practice and the rest of the women express aspirations to master it someday. Oral traditions and folksongs indicate that this intricate technique of back-strap loom was introduced by Chinese Princess Wencheng, known to the locals as ‘Ashi Jyazum’, back in the 7th century, and traces of her life remain as stories and heritage for Khoma.

Khoma alludes to a mundane atmosphere of village life mended with a reflection of solitude as the women concentrate on their crafts for hours. The first thing you hear after the break of dawn is the thumping sound of weaving echoing around the village as the sun embraces the valley. Several groups of looms are installed together making the sound of weaving stronger. Due to the long hours invested in weaving complex textiles, the locals express that they enjoy doing it together in groups, sharing a mutual bond and comfort. A life lived slowly, a craft through slowness, and a tradition preserved.

The locals welcome people who visit their village with utmost hospitality and they jubilantly engage in conversations. Sither Lhamo, the oldest weaver in the community at 86 years, was vigilantly weaving on her balcony on a brisk morning. Sither said, “I was going to stop weaving because I am old, yet I always find myself preparing another loom to weave again. I’m currently weaving this plain red raw silk textile for myself to wear in temples”. Sither’s life as one of the weavers was lived around this craft and in a speck of the time has become an ample part of her being. It is astonishing to comprehend what weaving means to these women and their collective dialogue. When asked why they like what they do, all of them answered that it was not just because of the income they make out of weaving, but more so because of the inherited tradition passed onto them for generations that they feel a proud and deep connection towards it.

Photography and words by Yeshey Choden – Commissioned by hima jomo

The Life and Legacy of Alexandra David-Néel

In 1924, Alexandra David-Néel made history as one of the first Western women to secretly enter Tibet. Disguised as a beggar, she crossed into Lhasa, bringing the mysteries of Tibetan Buddhism to the West.

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

Since 2023, HIMA JOMO has been steadfast in our pledge to plant a tree in the Himalayas for every perfume purchase made, join us in building a lush forest in the heart of the Himalayas with Nepal Evergreen.

The Travelling Jacket

In 2016, five designers from across South Asia came together to create what is now known as the traveling jacket.

The Himalayan Cedar

This majestic tree has captivated the hearts of explorers, poets, and nature enthusiasts for centuries with its enchanting presence, aromatic fragrance, and enduring qualities that make it a symbol of strength and grace.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Discover Ladakh: The Land of High Passes

India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means land of high passes.

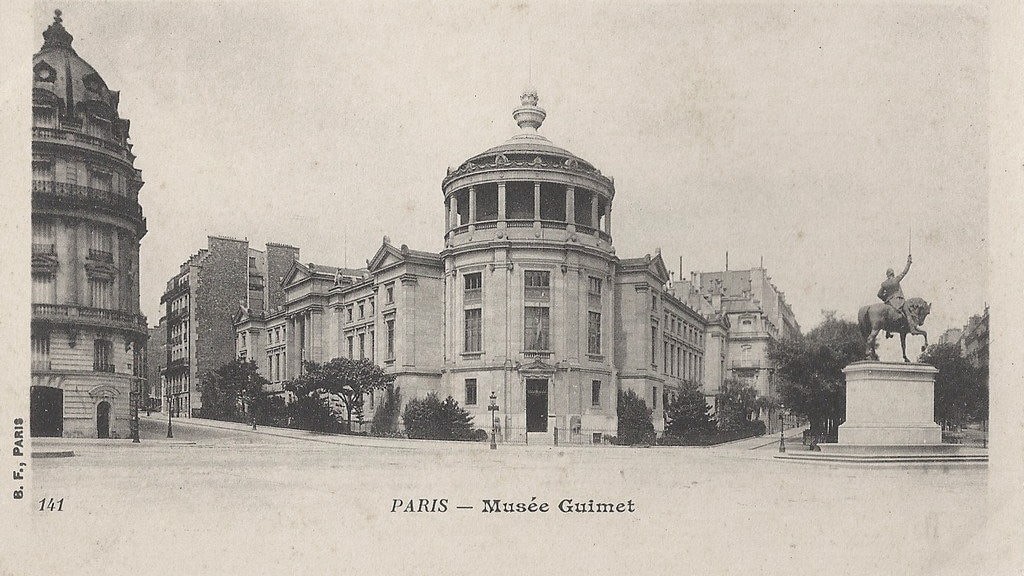

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.

The Power of a Thangka Painting

Thangkas are a distinctly Tibetan form of art centred around religious figures and symbols.