People of Dolpo live in the extremely remote villages of Nepal’s western highlands. Their lifestyle is not influenced by modernity and is close to a primitive one. Their lives depend on seasonal farming and petty trades; the people of Dolpo have accepted poverty in a way. However, even in such tough circumstances, Dolponians have proved to be the most content people on earth. Though a restricted region for tourists, Dolpo witnesses a few passionate travelers seeking unique cultural and natural experiences who wholeheartedly pay a heavy permit fee to explore Dolpo.

Dolpo (standard Tibetan: དོལ་པོ) is a high-altitude Tibetan cultural region in the upper-western part of Nepal, bordering the Ngari region of Tibet to the north. This remote region preserves Tibetan culture in its relatively pure form and has an irresistible appeal to Westerners. Dolpo was also the location for the 1999 Oscar-nominated film The Himalayas.

Dolpo is an area that is still inaccessible to travelers, and it is an adventure to enter this hidden land. The high mountains and valleys are so treacherous that it is still not accessible by road, and it takes days to walk from either Nepal or Tibet to reach it.

With Tibetan Buddhism predominating in the area, there are also distinct traces of Bön (བོན). Bön encompasses the various religious traditions that existed here before the arrival of Buddhism from northern India, which gradually incorporated various teachings from Buddhist texts.

It is like the end of the world, suspended between the sky and the earth at the heart of the Himalaya – a lost heaven protected by untouchable mountains. In these almost forgotten valleys, no trees can be seen growing, and only a few fragile trees are attached to the hills.

Since the time of their ancestors, the people of Dolpo have lived in close exchange with neighboring Tibet: they traveled to Tibet to collect salt from the high-altitude lakes and offered grain from their crops in exchange.

The basis of the Dolpo economy is the salt trade between Nepal and Tibet. People rely on yak carts to transport grain to Tibet in the summer and then return to the mountains of Nepal with the salt for trade. In winter, salt can be exchanged for grain, and people use sheep, goats, or horses to carry it to the south in exchange for rice and maize.

The women of Dolpo work on the land; they own it and the houses. When a family has a daughter and a son, the land belongs to the daughter, not the son. The women work from dawn to dusk but do not seem particularly tired, perhaps because they work together. They sing, chat, and joke as they work.

After dusk, multiple waves of people enter family life, all sitting around a wooden floor covered with blankets and a fire. Most families have no electricity supply, and the energy they get from solar cells is only enough for a short time. As a result, they usually don’t stay up late, go to other rooms, or sleep around the cooker shortly after eating.

The Dolpo women describe their lives like this:

“Every morning, we collect goat and sheep milk.

When we have a lot of milk, we are happy.

We make butter, we make yogurt.

In the evening, we share it with our neighbors.

When there is a lot of farm work to do, we help each other.

It is a good time to share; it is a good time to have tea and talk.

We often get together and have a lot of fun.

At first glance, people might think we are dirty.

But our hearts are clear, our souls are light and happy.

Some people are rich and have a lot of things, but I honestly would rather stay here.

Our land is very precious, and if you work hard, it will give you something in return.

The land is passed down from generation to generation, and you will always have it.”

Dolpo has a very beautiful culture, but many people here don’t realize it. They love life in Kathmandu and no longer understand the local culture. Some Dolpo people have left home since childhood to study and live in Kathmandu or India to experience the modernity of the outside world. Those people who have drifted away from Dolpo, but their souls still remain here.

The Life and Legacy of Alexandra David-Néel

In 1924, Alexandra David-Néel made history as one of the first Western women to secretly enter Tibet. Disguised as a beggar, she crossed into Lhasa, bringing the mysteries of Tibetan Buddhism to the West.

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

Since 2023, HIMA JOMO has been steadfast in our pledge to plant a tree in the Himalayas for every perfume purchase made, join us in building a lush forest in the heart of the Himalayas with Nepal Evergreen.

The Travelling Jacket

In 2016, five designers from across South Asia came together to create what is now known as the traveling jacket.

The Himalayan Cedar

This majestic tree has captivated the hearts of explorers, poets, and nature enthusiasts for centuries with its enchanting presence, aromatic fragrance, and enduring qualities that make it a symbol of strength and grace.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Khoma, the Sound of Weaving

A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

Discover Ladakh: The Land of High Passes

India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means land of high passes.

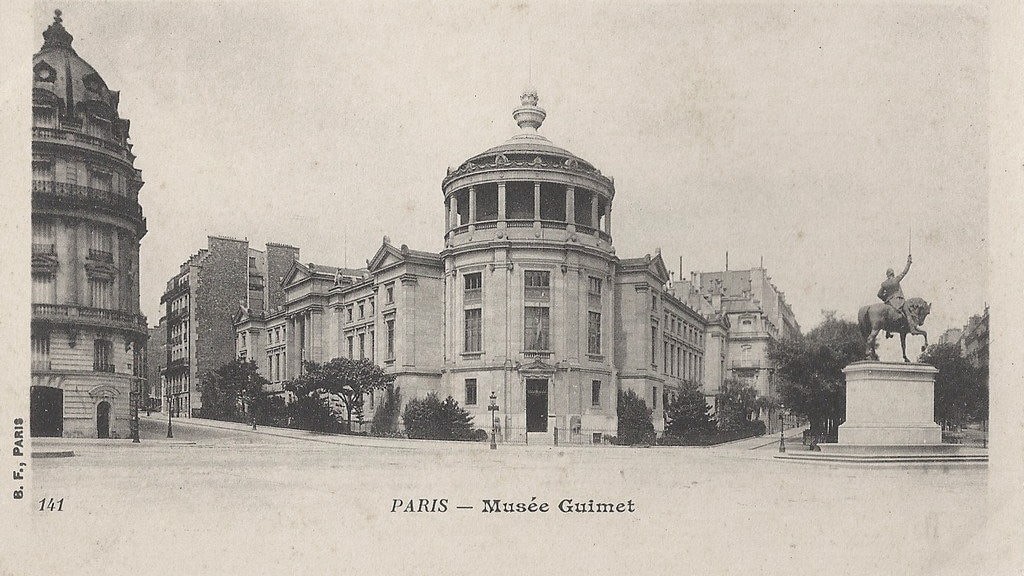

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.