This marked the onset of the most significant and fulfilling phase of David-Néel’s life. She underwent a physical transformation, evolving from a somewhat neurasthenic and unhealthy woman to one who appeared years younger.

Alexandra David-Néel with the Gomchen of Lachen in Sikkim (North), 1914.

Alexandra David-Néel was resolute in her pursuit of religious studies. Initially, she revisited India, where she predominantly encountered Hindus. She interviewed Sri Aurobindo and the widow of Sri Ramakrishna, engaging in lengthy discussions about religion with a Brahman. While entertained by the wealthy and prominent in India, she disdained the caste system and the misery it perpetuated. While intrigued by the philosophy of Hinduism, she was never drawn to it as a practice.

It was during her time in Sikkim that she encountered three individuals who profoundly influenced her life: Sidkeong Tulku, the maharajah of Sikkim; His Holiness the thirteenth Dalai Lama; and the Gomchen (“great meditator”) of Lachen. It was considered unusual—and somewhat socially inappropriate—for a Westerner to forge personal relationships with “natives,” but David-Néel didn’t hesitate, forming intimate friendships with Sidkeong and ultimately becoming a disciple of the Gomchen.

This marked the onset of the most significant and fulfilling phase of David-Néel’s life. She underwent a physical transformation, evolving from a somewhat neurasthenic and unhealthy woman to one who appeared years younger. Ruth Middleton, her primary English biographer, speculates that her time in the Himalayas was pivotal in these changes—”Her health improved dramatically above a certain altitude”—but it’s also noteworthy that David-Néel, who had been isolated from other Buddhists until then, found herself in an environment where she received support for her spiritual endeavors. When the Dalai Lama queried how she could have embraced Buddhism without a teacher, she responded, “When I adopted the tenets of Buddhism, I didn’t know a single Buddhist, and perhaps I was the only Buddhist in Paris.” During their initial conversation, the Gomchen of Lachen remarked, “You have seen the ultimate and supreme light. Achieving the concepts you express doesn’t happen after a year or two of meditation.”

In 1912, she penned a letter to Néel—whom she affectionately addressed as Mouchy—detailing her progress: “Each day, I find myself farther from the illusions and tumult (of the world). A profound tranquility, a profound enlightenment permeates me, or rather, I immerse myself in them. . . . You have a wife who carries your name with dignity. . . . With your support and assistance, I will become a renowned author.” Relocating to Benares, she dedicated long hours to studying Sanskrit, meditation, and learning from a Vedantist. After two years abroad, she began to realize a genuine conflict between her marriage and her spiritual aspirations. Understandably, Mouchy desired a conventional wife and intimate partner, whereas she sought a spiritual connection that he likely wouldn’t comprehend. In truth, while Sidkeong was committed to marrying another woman, she could have likely fostered such a relationship with him, and her residence at the Sikkim palace as his confidante wouldn’t have been entirely unconventional. However, the longer she remained distant from Néel, the more she valued his support. “I believe you are the only person in the world to whom I feel attached,” she wrote to him, “but I am not suited for married life.” She increasingly regarded solitude as the sole means to deepen her Buddhist practice.

In 1914, she resolved to relocate to the Gomchen of Lachen’s summer retreat. This revered hermitage, situated at 13,000 feet, was immortalized in Magic and Mystery in Tibet. There, she was attended by 14-year-old Aphur Yongden, her companion for the next four decades. However, during the early stages of her seclusion, she learned of Sidkeong’s passing. Devastated, as was the Gomchen—who viewed Sidkeong as Sikkim’s lone hope for religious reform—David-Néel dedicated herself to the Gomchen’s tutelage. He insisted she remain “completely at his disposal” for a year, a sacrifice she deemed worthwhile. Ultimately, she spent two years under his guidance, delving into tantric mysteries and mastering the Tibetan language.

By then, the First World War had erupted, rendering her return to Néel implausible (although her desires remained uncertain). In 1917, she journeyed to Japan, hopeful that Néel might join her and intrigued by Zen Buddhism. Renowned for her book Le Bouddhisme du Bouddha (The Buddhism of Buddha), she was celebrated as a luminary first in Japan, then in Korea and China. Yongden accompanied her, signifying his familial estrangement and unwavering commitment to her. In China, she encountered a Westerner who had undertaken the forbidden voyage to Lhasa, regaling her with his exploits. However, civil unrest in China compelled her to flee to Mongolia, where she resided at the Kumbum monastery, birthplace of the esteemed Tibetan sage Tsong-khapa.

David-Néel dedicated an entire chapter of Magic and Mystery in Tibet to Kumbum—an enclave where she led a life of study and contemplation that she cherished. Housing some 3,800 lamas, Kumbum offered the striking spectacle of their silent procession to the meditation hall before dawn for morning chants. She immersed herself in meditation and scholarly pursuits at Kumbum, transcribing works of Nagarjuna and translating the Prajnaparamita Sutra. Having spent a decade away from Europe, she resolved to delay her return until she fully explored Tibet. In particular, she aspired to become the first Western woman to enter Lhasa.

This achievement, above all others, catapulted David-Néel to fame, with My Journey to Lhasa emerging as her most renowned work, captivating readers regardless of their interest in Buddhism. She and Yongden embarked on the journey alone, posing as a lama and his elderly mother. Fluent in Tibetan and well-versed in the city they purported to hail from, David-Néel meticulously concealed her identity. Ruth Middleton recounts, “She darkened her brown hair with Chinese ink and ‘lengthened’ it with a yak’s tail. She darkened her already bronzed face and hands with soot scraped from the bottom of a caldron.”

They traversed the terrain on foot, often under the cover of night, narrowly evading detection on numerous occasions. Once, she found herself stranded midstream in a turbulent river, suspended by a rope. Twice, she and Yongden faced robbers, necessitating her to discharge her pistol to deter them. Negotiating a perilous route between two mountain passes, they risked starvation due to an unexpected snowfall. Nonetheless, their arrival in Lhasa, followed by a two-month sojourn, proved anticlimactic. The journey itself constituted the triumph.

David-Néel’s return to Europe, following the war’s conclusion, proved as unconventional as her preceding exploits. While the 60-year-old Néel entertained hopes of rekindling his marriage to Alexandra, he couldn’t fathom why she was accompanied by Yongden, let alone considering him an adopted son. Even upon her return, reuniting with her husband proved challenging, prompting her and Yongden to settle in Provence, where she thrived as a writer and lecturer, renowned for her adventures. Regardless of the nature of her relationship with Yongden, it’s noteworthy that she ultimately settled down with someone who posed no threat to her independence. Nevertheless, she harbored hopes that Néel would join them. Upon his demise in 1941, she lamented, “I have lost the best of husbands and my only friend”—a sentiment somewhat dubious and perplexing regarding her devotion. Even more devastating was Yongden’s demise due to uremic poisoning in 1955. Fortunately, in 1959, she found solace in Marie-Madeleine Peyronnet, an exemplary secretary who remained her companion during the twilight of her life, maintaining a museum in her honor posthumously.

To the Tibetans, Alexandra David-Néel’s pilgrimage to Lhasa seemed natural: she was revisiting the site of a past incarnation. From a Western standpoint, her interest in Buddhism during her era was remarkable, let alone her firsthand exploration of the East. Equally astounding was her tenure as an independent scholar, bereft of institutional backing.

While renowned as an adventuress, this designation fails to encapsulate David-Néel’s true achievements. She left behind copious writings, many of which remain untranslated into English, resonating not solely due to her erudition but also her lifelong spiritual journey. A woman who spent years in seclusion atop a mountain, who meditated alongside thousands of lamas, who immersed herself in languages and combed through libraries for original teachings, and who traversed vast distances over many years to immerse herself in a culture unfamiliar to most, offers insights far beyond those gleaned solely from books. Her unwavering commitment to Buddhism and her determination to trace it to its origins ultimately emerge as the most compelling facets of her life.

Words by David Guy

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

Since 2023, HIMA JOMO has been steadfast in our pledge to plant a tree in the Himalayas for every perfume purchase made, join us in building a lush forest in the heart of the Himalayas with Nepal Evergreen.

The Travelling Jacket

In 2016, five designers from across South Asia came together to create what is now known as the traveling jacket.

The Himalayan Cedar

This majestic tree has captivated the hearts of explorers, poets, and nature enthusiasts for centuries with its enchanting presence, aromatic fragrance, and enduring qualities that make it a symbol of strength and grace.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Khoma, the Sound of Weaving

A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

Discover Ladakh: The Land of High Passes

India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means land of high passes.

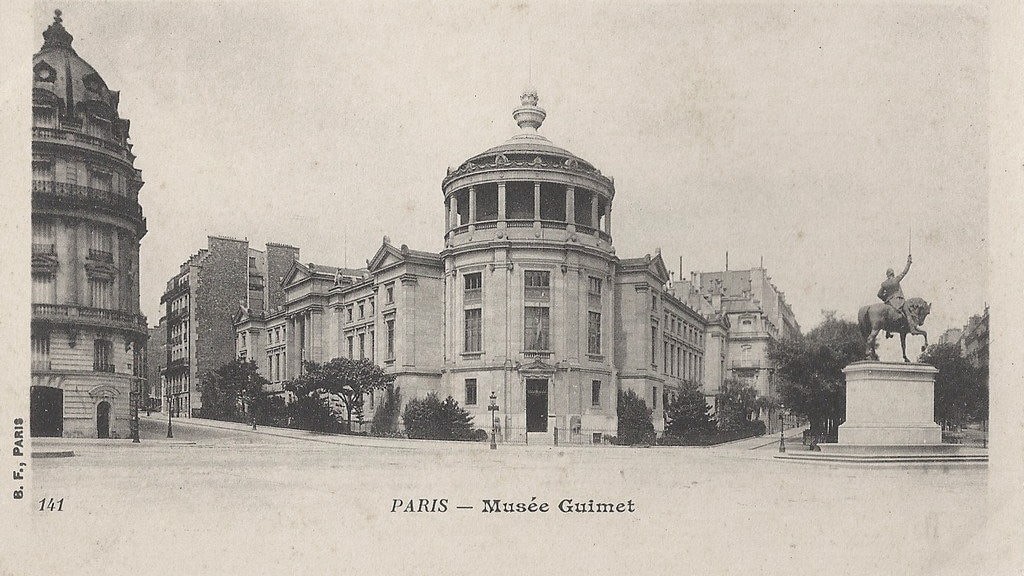

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.

The Power of a Thangka Painting

Thangkas are a distinctly Tibetan form of art centred around religious figures and symbols.