Alexandra David-Néel lived for a century. She was born in France in 1868, during the period of la belle époque, and passed away in 1969, shortly after the student riots in Paris. In between, she spent fourteen years studying Buddhism in Asia and, at the age of 55, became the first Western woman to enter the Tibetan city of Lhasa.

It is tempting to think that she was born too soon, but so free and bold a female spirit would have encountered obstacles anywhere, at any time. At the age of 16, she was already running away from home for jaunts across Europe, and she traveled to India at 21. Her early adulthood was consumed by a career as an opera singer—an ample accomplishment for an ordinary life but almost overlooked in hers.

It was not until middle age that she married Philippe Néel, the French engineer who supported her through her subsequent adventures, but with whom she almost never lived. Néel did not understand his wife’s interest in Buddhism and the East, but in 1910, he offered her a “long voyage”—he meant something like a year—to “get it out of her system.” She was gone for fourteen years, traveling and living in India, Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, China, Japan, making forays into the forbidden kingdom of Tibet. On her return to Europe, she was celebrated as an adventuress and lived another 45 years as a lecturer and writer. She left four projects unfinished when she died just short of her 101st birthday.

In an age when even those sympathetic to the East were mostly dabblers or lovers of the occult, Alexandra David-Néel distinguished herself both as a scholar and a practitioner. The style of her day was to examine things dispassionately and objectively, but David-Néel experienced them personally and, in such books as My Journey to Lhasa and Magic and Mystery in Tibet, wrote about them the same way.

Alexandra’s father, Louis David, was a French Protestant, a Huguenot, a socialist, and a Freemason. He opposed the monarchy of Louis Philippe, participated in the Revolution of 1848, and fled to Belgium with his friend and compatriot, the novelist Victor Hugo. There he fell in love with Alexandrine Borghmans, a devout Roman Catholic who supported the Belgian monarchy and who in many ways was his opposite. They married, and eventually moved back to France, and 13 years passed before they had their first child. Mme. David was bitterly disappointed that Alexandra was not a boy and paid almost no attention to her.

“Ever since I was five years old,” David-Néel wrote in My Journey to Lhasa, “I wished to move out of the narrow limits in which, like all children of my age, I was then kept. I craved to go beyond the garden gate, to follow the road that passed it by, and to set out for the Unknown. But strangely enough, this ‘Unknown’ fancied by my baby mind always turned out to be a solitary spot where I could sit alone, with no one near.”

At the age of 16—in an era when such behavior was scandalous for a girl—she ran away from her family home in Brussels several times, once to Holland and England, once to Italy, then later through France and Spain. She had taken an interest in religion from an early age, and a schoolgirl friend gave her a review entitled Gnose Supreme (supreme knowledge) published by an English occult society. When she determined at the age of 18 to study English in London, she contacted a Mrs. Morgan at the Society of the Gnose Supreme and arranged to stay there. She spent long hours in the Society’s library, poring over translations of Chinese and Indian texts.

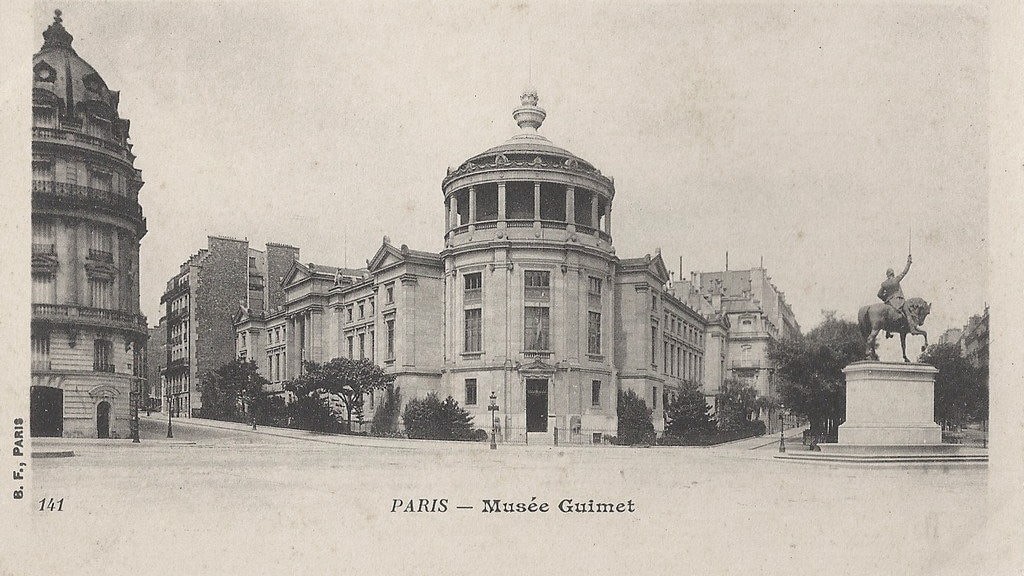

When David-Néel decided to continue her studies in Paris, Mrs. Morgan arranged for her to stay at the Paris branch of the Theosophical Society. Though she found the Theosophical Society not to her taste, she discovered its excellent library, where she first read about Tibetan Buddhism. She also discovered the Musée Guimet, whose Asian collection—renowned to this day—intensified her attraction to the East. One day, believing herself to be alone in the museum, she bowed to a large Japanese statue of the Buddha, and a voice said, “May the blessing of Buddha be with you, Mademoiselle.” That voice turned out to belong to the Comtesse de Breant, who introduced her to other Parisians with an interest in the occult.

By the age of 21, David-Néel had become a devoted linguist, and when she decided to spend a legacy from her godmother on a trip to India, it was in order to pursue her study of Sanskrit. When she returned to Europe penniless, however, she ran head-on into the limitations of her gender. She had begun writing and had published articles on her travels and studies, but they paid little, and a career as a professor was not open to her. She had always shown talent in music—a field that was available to women—so she studied seriously and began a career as an opera singer, returning to the East for a while as the première cantatrice in the Opera Company of Hanoi. During some of this period, she lived openly with the Belgian composer Jean Haustont, a fact of which her freethinking father was apparently aware.

David-Néel’s relationship to men was enigmatic throughout her life. Her biographers have variously said that she was repulsed by sex because she didn’t receive enough physical affection as a child and that she detested all things masculine. It is an undeniable fact that when she finally married she spent almost no time with her husband. Yet it is also true that all her spiritual teachers were male, and that the closest thing she ever found to a lifetime companion was a young lama, thought by some to be her lover (although there is no concrete evidence of this), whom she eventually adopted as a son.

It seems possible that she was repelled not by sex or men but by the sexual mores of her culture, in which women functioned as decorative appendages for men, and in which men raised families with their wives but found sexual gratification elsewhere. What David-Néel may really have wanted—even before she knew it—was a spiritual connection with a man, which she didn’t find until she traveled to the East. Her acceptance of marriage before that may have been an attempt to find the financial stability that she needed for her studies. In any case, at the age of 36, she married Philippe Néel, a well-off engineer who, despite his reputation as a philanderer, was considered quite a catch.

The early months of marriage—during which she was often apart from her husband, pursuing her writing career—were difficult. Her letters and journal entries reflect considerable torment about her husband’s wayward past and ambivalence about her role as wife. She was also becoming more and more interested in Buddhism, writing in her diary of “the delicious hour of perfect detachment and intimate joy” when she meditated. Néel, who was somewhat sympathetic to her feelings, offered her the “long voyage” to the East.

Words by David Guy

Earth Day – Our Environmental Initiatives

The Himalayan Musk Deer is a small, elusive deer species known for its unique appearance and the musk secretion it produces.

The Travelling Jacket

The Himalayan Musk Deer is a small, elusive deer species known for its unique appearance and the musk secretion it produces.

The Himalayan Cedar

The Himalayan Musk Deer is a small, elusive deer species known for its unique appearance and the musk secretion it produces.

Earth Day with a Himalayan Kingdom

Earth Day, a cherished moment that comes each year on April twenty-second, is a worldwide communion of hearts, minds, and hands, united in a shared reverence for our planet's splendour.

The blue poppy of the Himalayas

A flower that lives in the seclusion of the nature that surrounds her. Simply known as blue poppy but its colour speaks silent poetry.

Khoma, the Sound of Weaving

A collective thumping sound echoes in the village of Khoma with the wake-up call from their local roasters.

Discover Ladakh: The Land of High Passes

India is known globally for its vibrant and bustling megacities but in its northern reaches lie the mountains and valleys of Ladakh, a name that means land of high passes.

Five Millenia of Asian Art at Paris’ Musée Guimet

Works of art that have survived the test of time offer us clues about the history and culture of past generations and civilisations.

The Power of a Thangka Painting

Thangkas are a distinctly Tibetan form of art centred around religious figures and symbols.